THE RECIPE FOR ALL GOOD THINGS

Storytelling/Writing/Memoir

The theme for last year’s SBS Emerging Writers’ competition was ‘Between Two Worlds’, so I decided to write about my experience of growing up biracial, Western beauty standards, Asian mother-daughter relationships and the messiness of it all. Somehow rendang (a spicy Indonesian dish) and nipple anxiety ended up being at the centre of my story (I’m just as surprised as you are).

Read the edited version published on SBS Voices here

Rendang! (Image borrowed from Ang Sarap)

I was 14 when my life became less about swim training and more about my waistline. I’d won a modelling competition that got me noticed, which made no sense at all, because up until that point, I’d been doing everything in my mind to fit in.

“Have we been enjoying too much of mum’s curry?” he asked.

I laughed the question off, but something about it hit a nerve. Sadly, the answer to that question was no. I was ‘bigger’ because I was sick of my rabbit diet. Later that night, I wondered if Mum’s rendang was a curry.

This was one of many painful measurements I’d have with my modelling agency. Check-ins to make sure I was growing in all the right places. I dreaded them. Not only were they a reminder of all your physical flaws and failures, they made you walk up three flights of stairs just to see them. Another sadistic attempt to trim the fat and make you really hate yourself for loving pizza. Despite the anxiety-induced butt sweat and inability to grip the railings, I always managed to drag myself to the top, ready for the next round of swipes at my dignity.

What interested them was our racial ambiguity – not quite white, not quite ‘other’. In business terms, ‘safe’ enough for the supposedly white Australian market.

It was the early 2000’s and Perth was making waves in the modelling world. ‘There’s something in the water!’ they’d say. Indeed there was – a sea of blonde, white, waify types with perfect height and perfect cup sizes. But there was also a brunette with pouty lips and olive skin getting attention. She was ‘exotic’. And so was I, apparently. My agency wanted me to be version 2.0. To be accurate we were biracial, a minor detail. What interested them was our racial ambiguity – not quite white, not quite ‘other’. In business terms, ‘safe’ enough for the supposedly white Australian market. But there wasn’t room for all of us. Especially if your measurements were pushing Height: 5’8, Bust: 33B, Hip: 36”, when really you were “Height: 5'7, Bust: 32A Hip: 40”. I’ve always hated the Imperial system.

A year before the competition, I’d just started modelling classes. My mum had been trying to get me to join for months but my answer was always no. My default mode was to be polar opposite to her in every way, whenever I could. It wasn’t until a family friend started classes that I gave in. My friend was a halfie like me and she got what it was like having an overbearing Asian Mum. Despite the strictness, she seemed totally unaffected: free-spirited, fun and confident in her own skin. It was like she had mastered the art of living in two worlds.

![]()

![]()

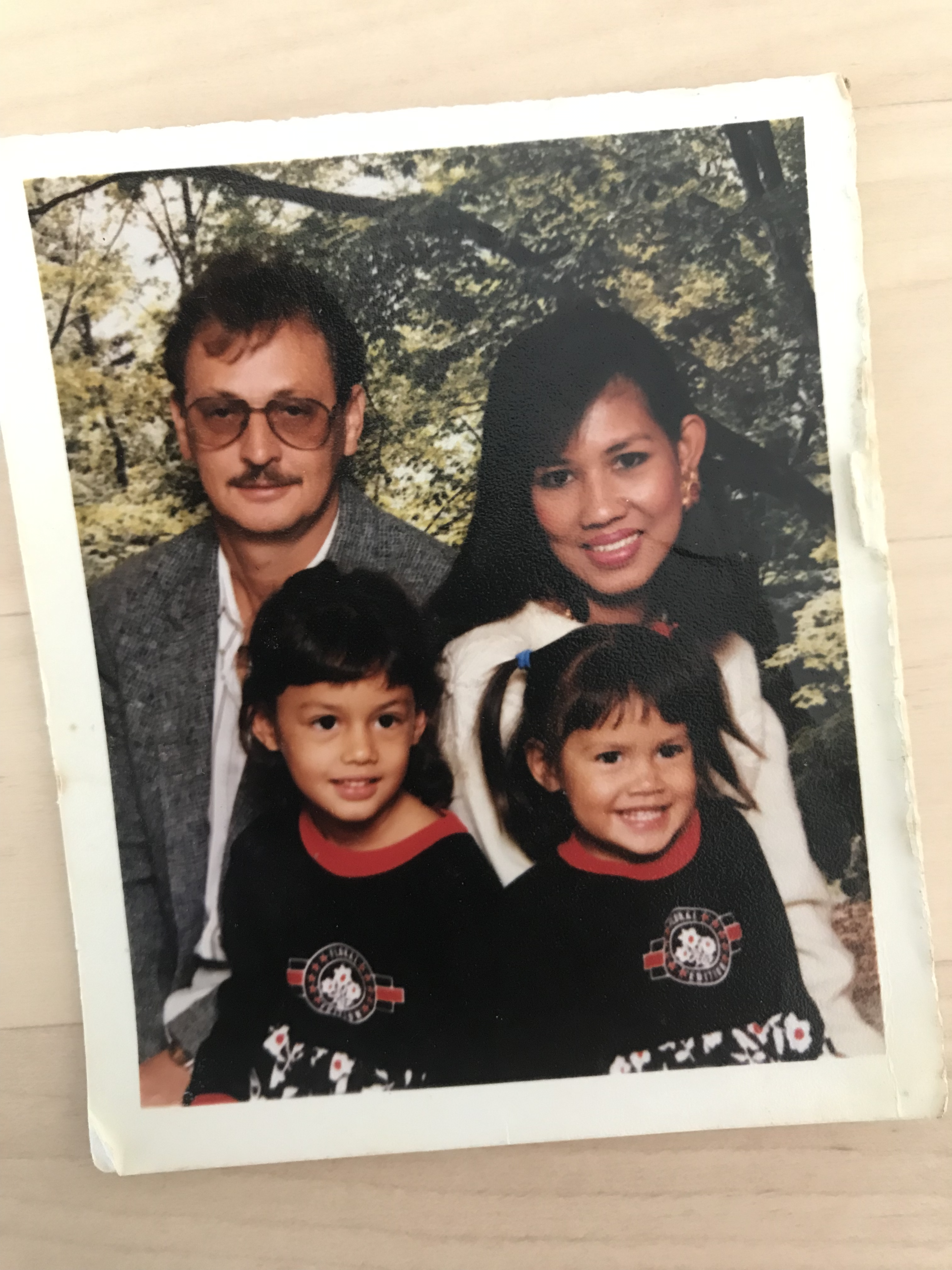

Left: A family portrait (when we lived in Brunei) “Have we been enjoying too much of mum’s curry?” he asked.

I laughed the question off, but something about it hit a nerve. Sadly, the answer to that question was no. I was ‘bigger’ because I was sick of my rabbit diet. Later that night, I wondered if Mum’s rendang was a curry.

This was one of many painful measurements I’d have with my modelling agency. Check-ins to make sure I was growing in all the right places. I dreaded them. Not only were they a reminder of all your physical flaws and failures, they made you walk up three flights of stairs just to see them. Another sadistic attempt to trim the fat and make you really hate yourself for loving pizza. Despite the anxiety-induced butt sweat and inability to grip the railings, I always managed to drag myself to the top, ready for the next round of swipes at my dignity.

What interested them was our racial ambiguity – not quite white, not quite ‘other’. In business terms, ‘safe’ enough for the supposedly white Australian market.

It was the early 2000’s and Perth was making waves in the modelling world. ‘There’s something in the water!’ they’d say. Indeed there was – a sea of blonde, white, waify types with perfect height and perfect cup sizes. But there was also a brunette with pouty lips and olive skin getting attention. She was ‘exotic’. And so was I, apparently. My agency wanted me to be version 2.0. To be accurate we were biracial, a minor detail. What interested them was our racial ambiguity – not quite white, not quite ‘other’. In business terms, ‘safe’ enough for the supposedly white Australian market. But there wasn’t room for all of us. Especially if your measurements were pushing Height: 5’8, Bust: 33B, Hip: 36”, when really you were “Height: 5'7, Bust: 32A Hip: 40”. I’ve always hated the Imperial system.

A year before the competition, I’d just started modelling classes. My mum had been trying to get me to join for months but my answer was always no. My default mode was to be polar opposite to her in every way, whenever I could. It wasn’t until a family friend started classes that I gave in. My friend was a halfie like me and she got what it was like having an overbearing Asian Mum. Despite the strictness, she seemed totally unaffected: free-spirited, fun and confident in her own skin. It was like she had mastered the art of living in two worlds.

Right: Me, Mum and my older sister (New Zealand 1992)

Our bonds went back to Hari Raya Aidilfitri, a religious holiday that celebrates the end of fasting. Every year we’d pray with her fam in a cleared out rec-centre with other Indonesians after sunrise. We were the last to arrive ‘jam karet’ style, even in Perth traffic and the first to leave. We then dragged our parents to Maccas so we could line our stomachs with hotcakes before the real feast started – the Indonesian version of a pub crawl. Instead of pubs we visited aunties, and instead of crawling, we hobbled from overeating rendang. It was worth it. It’d be another year before we got to eat that kind of food again.

All the Aunties would gossip, all the white dads would sit awkwardly together in the garden and all us brats would compete over who had the craziest mum. Like who got grounded over the dumbest shit; who got smacked with a ‘sapu lidi’ for talking back; whose mum wasn’t afraid to scold them in public and whose mum bragged about their kids the most – all me at one point – painful at the time but completely worth it just to laugh in hindsight and feel seen. It was tradition.

Every interaction we had was tricky. Every outing was a course to navigate. There was no hiding. Just me with my fire extinguishers, ready to put out her flames.

It wasn’t that we didn’t love our mums. It’s that we didn't understand them and they didn’t understand us. At least it felt that way. My mum had it tough growing up. She never had the luxuries or opportunities I was given as a kid and she loved to remind me of that fact. She was resilient, tenacious and would never take ‘no’ for an answer. Qualities that served her well in a world that wouldn’t make space for her, but not for this pubescent teen living in a bubble. Naturally, my mum wasn’t everyone’s cuppa tea and I hated this about her. Why couldn’t she be softer? More patient? More agreeable? More like my (white) friend's parents. Every interaction we had was tricky. Every outing was a course to navigate. There was no hiding. Just me with my fire extinguishers, ready to put out her flames. She’d always say:

“Why you try change mum? Why you so embarrass?!”

And I’d always say:

“Why are you always so difficult?! Why can’t you be normal!”.

A lot of door slamming would ensue. My Dad and sister would play umpire. The Asian stereotype of the quiet and subservient women always confused me. Sure, from the perspective of a Bule (white person) visiting Bali. But not the Indonesians I knew. Especially not my mum. She had fire in her belly. She was from Padang, a place known for its fiery rendang and fiery matriarchs in equal measure.

We clashed over everything. We couldn’t even have a conversation without one person rolling their eyes or interrupting the other. It was an Indonesian soap opera in our house every night. We had nothing in common, except modelling. For the first time our relationship felt manageable, so I went along with it.

‘Mum always wanted to be model’.

‘Mum, stop referring to yourself in third person’.

‘Mum wish I had your pointy nose’.

She would repeat the story of how I had a flat nose as a toddler and then one day…

‘mancuuuuuung hidung nyah!’

At this point she would pinch my nose (as did all my relatives in Indo)

‘You so beautiful my dear, you don’t know. And you so tall! Mum cannot wear that’.

‘They’re just pants’

‘And your lips...’

‘Stop mum!’

I hated when she went on her complimenting spirals. They made me self-conscious. Besides, I hated my lips. I wanted thin lips like Gemma Ward. I remember biting my bottom lip just to make it look smaller.

‘You get from me! Like Angeline Jolie’

‘Oh god, I’m leaving now.’

Mum and me sight-seeing between castings (Sydney, 2005).

My mum adored me. Her heart was in the right place but I now realise her compliments were always about my whiter features. It’s not that my mum thought Indonesians weren’t beautiful. Far from it. I think whiter features meant more than just skin. They meant wealth, class, and opportunities – perhaps the after-effects of colonialism rooted in the collective subconscious. These internalised ideals were reinforced everywhere. You wouldn’t have to look far to find skin whitening creams and almost every model or actor on screen was fairer or biracial. I don’t think my Mum was aware of her view of beauty. And to be honest, neither was I.

These ideals about beauty didn’t stop there. I remember the day my friend of Indian heritage told me a boy at school had called her a gorilla. I was entrusted with plucking her eyebrows – a task only reserved for true best friends. She was devastated, as was I. Back then, unwanted body hair was one of the many strange things we bonded over. Like the fact that we could both grow a moustache if we wanted to, or that we felt a little ‘different’ from the other kids. We’d both grown up in Asia and had moved to Australia in our pre-teens. Being on the receiving end of bullying came with the territory. We’d learned the trick to immunity: don’t stand out, don’t be different. But every now and then something would catch you off guard.

‘Whoahhh, look at those nipples!’

Every body part was fair game. Not only was the baseline of beauty being as hairless as a dolphin, but being lighter in places the sun didn’t shine.

My ears pricked up. The boys in high school were ruthless. Every body part was fair game. Not only was the baseline of beauty being as hairless as a dolphin, but being lighter in places the sun didn’t shine. There was a group of boys crowding over and laughing at an image of a woman’s brown nipples.

“Ewww grosss”.

From that day I was obsessed with comparing my nipples to everyone else’s. They were darker than my mums, my sisters, my dads, a half Asian boy I spied at the school swimming pool. They were darker than every model that bared their breasts for fashion, the movies or the internet. They were darker than all my friends’. I had no one left to compare them to. All I knew was that they looked the same colour as that image those boys had shared and I HATED them. I had an active imagination and the thoughts got worse. What if I have a kid one day? They’ll get BIGGER and DARKER. How am I going to get a husband? Wait, how am I going to get a boyfriend? I can’t hide them forever. Maybe I can? My body image was spiralling and modelling was only fueling it.

My nipple mania hit its peak at the worst shoot of my life. We were taking shots for my folio. It was part of another modelling competition my mum forced me to enter: A low-fi version of ‘Search for a Supermodel’ with 2-days of makeovers, bootcamp and a show at Fashion Week, then they announce a winner. It started off well. I followed the photographer's direction, we got the shots in under 15 minutes. I was on fire! And then he showed me the images...I could feel my butt sweat. In nearly every photo the flesh of my left nipple was staring back at me, mocking me through an intentional split along the lining of my top. You almost couldn’t see it but I couldn’t let it go.

‘I think my nipple is showing?’

‘Oh yeah, I didn’t want to say anything. You were doing so well.’

I could die a million deaths. I didn’t know how to assert myself and I didn’t want to ruin my chances of winning. I was crushed, my primary school days of being bullied came flashing back.

Looking back, the whole situation was pretty comical, but also just sad. Here was a 40-something year-old man photographing my 15 year-old nipples and all I could think about was how ugly they were.

Eventually I quit modelling. I couldn’t lose the weight and trying to be good enough was exhausting. I felt like a failure for years, plagued by all the ‘what ifs’: what if I had stuck with the diet long enough, could I have ‘made it’ in modelling? Would I be happier? Would my mum and I be closer? All deluded thoughts that distracted me from the questions I should have been asking: what if I stopped worrying about what people think? What If I stopped trying to change my Mum? What If instead I embraced her? I would only find the answers after years of unlearning and living on different sides of the country, away from my only cheerleader, my behind-the-scenes champion.

We’re now closer than we’ve ever been. We don’t talk about modelling anymore, we talk about Indonesian food. We still have heated chats, especially when she’s explaining a recipe over the phone.

‘You look and then you know’

‘How am I supposed to know?! I’ve never made it before!’

Going off feeling, not measurements – perhaps that’s the recipe for all good things. If I could go back in time, I know exactly what I would say to my agent:

‘It’s not a curry. It’s rendang and it’s fucking spicy. You should try it.’

Mum and me (Korea 2018).

︎︎︎ Back Next ︎︎︎